WW2 People's War

Below are a number of accounts written by people associated with Eaton Bray and submitted to the BBC's WW2 People's War archive, or direct to this website.

- Eaton Bray, A Childhood Memory, Bernard Dodd

- Village in War Time, Linda Potton

- My Childhood at Whipsnade Zoo, Lucy Pendar

- Abroad for the First Time, Stuart Hammond

- Farming and Life on Dunstable Downs, Derek Bonfield

- War Memories, J C Horne

- A Comptometer Operator in Dunstable, Mary Cumberland

- My Childhood in Totternhoe, Bedfordshire, Alan Wilsher

- Village Life, Jim Knight

- Childhood Memories of Wartime Dunstable, Albert and Patricia Morgan

Acknowledgments

WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

Eaton Bray, A Childhood Memory

Me at 3 years old in Bower Lane

It was WW2, though at the time I was too young to understand, Mother used to take me from our home near Coventry to stay at my Grandfather Taylor's house at Eaton Bray. I knew my Dad was away in the army, and Uncle Jim's street in Coventry was bombed, mother always said we were safer at Eaton Bray.

I remember catching the trains in those far off days, We used to change at Bletchley, then at Leighton Buzzard, it would often take most of the day to travel the 50 miles or so to Dunstable station after which we would walk up the town's busy Main Street to near a place called the Sugar Loaf, a Pub or Hotel? I never knew, to get the bus to Eaton Bray. We would ride on a big green double deck bus. As a child I loved them, especially riding on the top deck, I had never seen green buses before let alone double deck ones, they were so different to our local red single deck ones at home, though at the time many were in wartime black. We would get off at the Chequers Inn.

Grandfather lived at 57 Bower Lane, was there really 29 houses on that side of the street? It was the last house in the long terrace on the left as we walked up the street.

The house was small, 2 bedrooms, 2 living rooms and a tiny kitchen, the toilet was quite a walk down the back yard to where a block of them took care of the needs of the whole row of houses. Bath night was an unusual affair, I had to go to No. 53 and joined the two children who lived there, a boy and a girl, in a tin bath by the fire. Sadly I no longer remember their names. Each house had a back garden where I remember lines of washing but little else about the gardens except playing in them. Next to 57 was an orchard and then further along the street a pub, the Hope and Anchor where like the Chequers at the bottom of the road we would go and sit in the garden, little me with a glass of pop and if I was lucky some crisps. Further up Bower Lane on the other side of the road there were a few council houses and mother's adopted brother, Uncle Frank, lived in the farthest one. Over the next 4 or 5 years I would spend much time with Frank wandering around the wonderful countryside catching rabbits, looking for pheasants eggs, fishing near the ford at Edlesborough or even going to Bookers Pig and Poultry farm on the Downs where he worked for a while. Frank rode a bike and I was transported on the crossbar.

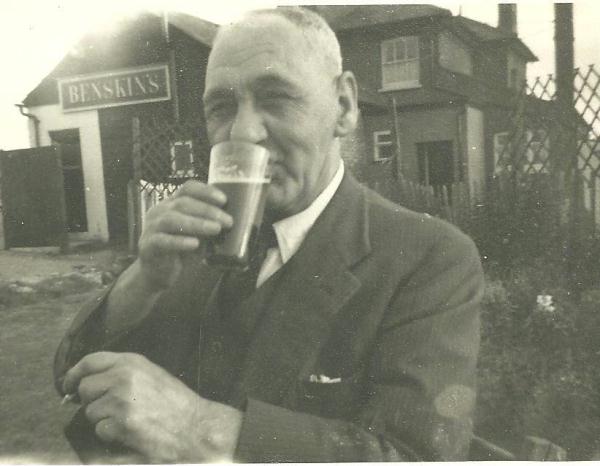

Jos Taylor, my grandfather in his garden at 57 Bower Lane

Though I was only a few years old and was only in Eaton Bray for a relatively short time of my life, I seem to recall many things with still many unanswered questions.

The soldiers marching down the street, mother would tell me to go and see if dad was with them, later as I grew up I realised she knew he wasn't but also have wondered where those soldiers came from, was there an Army camp on the Downs?

The old Yew Tree farm down the road I remember constantly going there but for what? Did they sell milk or vegetables or was there another reason?

There were two other pubs we used to go to, the White Horse was one yet I recall little else of that part of the village, the other was the Axe and Compass at Edlesborough, did these pubs all have outdoor seating for families that made them so special?

Edlesborough was where strangely mother seemed to buy most of the groceries at a little shop where the lady often said she had some Spam !!! why was it so special? I have never found out.

Then I remember a lovely waterfall and stream running through a beautiful garden and the AC factory where my grandfather had once worked, were they in Eaton Bray or Edlesborough? I do not know.

There was the hot day when mother decided to walk up to Whipsnade, we often went there though I am not sure why so often, although it was hot with a clear blue sky grandfather took his huge old black umbrella, mother laughed at him but was to thank him much later in the day when the heavens opened up to a thunderstorm. A walk up to Whipsnade would often mean a glass of pop for me at another pub on the cross roads, the Halfway House before continuing our walk home, is it still there I wonder.

During the times I went to Grandfather's I became friendly with the local children and I had a cousin of similar age, Christine, Uncle franks daughter. We used to make our own amusement simply by walking or fishing in the ford, seem to remember an old mill nearby, bent pin, cotton, stick and some bits of worm and many sticklebacks and minnows could be caught and placed in the compulsory jam jar, also used for keeping butterflies in at other times, Uncle Frank had taught me rightly or wrongly how to supplement war rations with eggs from pheasant, pigeon and moorhen nests in the spring, to net pigeons or snare rabbits for meat, what berries and wild fruits to pick, we always had plenty to eat.

The war had ended, I was 7 years old but I had learnt a lot, dad was home safe from the war, our visits to Eaton Bray got fewer, grandmother Taylor who had been the backbone of the Bower Lane household through the war, she had proved capable of making fantastic meals from some most amazing recipes with a variety of ingredients from wild mushrooms, pigeons, Spam, nettles etc etc, passed away, her grave is in the local graveyard. Mother decided her father was to come and live with us in the Midlands. The furniture was sold or given away, a gold sovereign was found, I think grandfather got more for it than the furniture. The 3 gramophone records were kept, Turkish Patrol, Teddy Bears Picnic, and Blaze Away, we had played them 100s of times on an old windup machine, though sadly they would not last much longer.

We made our last visits to some of the pubs....

Grandfather's last pint at Eaton Bray, was this the Chequers or the Hope and Anchor?

We said our goodbyes to friends and neighbours and to Uncle Frank and his wife Aunt Gwen and to cousin Christine piled into dad's old car and left. We were to lose touch with everybody at Eaton Bray even our relatives.

Some years ago my wife and I visited the village, although things had changed we had a lovely meal in the Hope and Anchor and I was able to recall a few places. Recently we returned, so much has changed, the Chequers long gone the orchards in Bower Lane have gone replaced with houses and the Hope and Anchor, well we passed on by. I just decided to keep my childhood memories.

Village in War Time

Contributed 8 September 2004 by Linda Potton

Contributed 8 September 2004 by Linda Potton

There were four sisters in Bermondsey - my mum and three aunties. The eldest, lived in Eaton Bray. My mother, because when the sirens went my six year old brother would run into the Church crypt, and my mother had to grab me, the baby and go and look for him. So they suggested that they all went to Eaton Bray for safety, as the eldest sister lived there.

While the others went to work my mother was left with all the children in this cottage without electricity so she paid to have it put herself. One sister went on the buses as a Clippie, I went to A.C. Delco on war work. But the eldest sister went into the School House as a Caretaker, and had a small garden with a pig, chickens and vegetables. She also took in lodgers who were doing war work. People came from London for short visits for respite.

My Childhood at Whipsnade Zoo

Contributed 4 May 2005 by Lucy Pendar

Contributed 4 May 2005 by Lucy Pendar

I was eleven years old when war broke out; my father was a resident engineer at Whipsnade Zoo and as a result we lived in the park grounds with my parents, my mother's mother, my father's brother's wife and her nine month old baby. I was sitting on some steps playing marbles with some friends when a very important gentlemen came up to us, most people would have just told us to get out of the way but his gentleman asked us to move very politely. When he came out we were told that war had been declared and we went home to get our gas masks - contained in a little cardboard boxes held with string. The first thing to happen was that the policeman was sent round on his bicycle informing everyone that the park would be closing. As we had nothing to do we were offered riding lessons on the Shetland pony!

Two elephants were sent to Whipsnade while a new elephant house was being built in London Zoo. They were soon joined by another three evacuee elephants from London together with the senior elephant keeper and his wife, who were housed in a cottage in the village. Three giant pandas arrived at Whipsnade during the summer and kept in a pen where the new chimp island has now been built. They chewed on bamboo, which was grown especially for them in Cornwall. Four chimps and two orangatangs were sent down with the senior chimp keeper and his family who were housed in a cottage in the car park. Wives and children of the Zoological Society were also evacuated and housed in old army huts in the village.

With all the evacuees in the village, the superintendent's wife formed a guide company. We were taught Morse code and were so good that we won the district award for it. Of course guiding meant service so we collected rubbish and filled sandbags. I was sent to look after toddlers in a nursery behind the Catholic Church but I didn't relate to small children very well and spent my time chatting up the catholic priests. I didn't know at that time they had to be celibate and I wouldn't get anywhere!

The guides belonged to the Dunstable Association of Youth Organisations and held swimming galas at the California pool in Dunstable. I was lucky enough to be the swimming champion. My little highlight of the war at the California happened when a man was in difficulty, his wife was shouting and I plunged in, grabbed hold of him and pulled him out. When he thanked me for rescuing him, to my astonishment he was dressed in a sailors uniform!

We went on parades in Dunstable with the army and air cadets. We had war ship week and wings for victory week and would stage plays and concerts in Whipsnade village hall to raise money. We also had a national savings competition. We did so well that they put a flag pole up in the village grounds and let us take turns to hoist the flag. I wasn't very long before most of the wives and children evacuated went back to London but there were still enough children for us to have parties and a social life, which was totally non existent before the war.

The government regulations stated that a certain amount of grassland should be se aside for growing food. The park had always made its own hay but now the old farmland (because the zoo had been a farm before it was a zoo), found parts of itself, back to its old use. Potatoes and root crops were used to supply the restaurant and used as animal feed, the grass made hay, domestic animals were breed on the farm, pigs and sheep were sold to the ministry of food while some pigs were sold to the Herts and Beds bacon factory at Hitchin.

During the time of rationing, if local people could afford it, they would come to Whipsnade for Sunday lunch for the price of 3 shillings and 6 pence. It meant they could save their coupons and I remember one of the people who came was Phyllis Calvert, the actress. She had a house in Kensworth and would walk with her husband and children to have their lunch at Whipsnade.

Our meat ration as a family was supplemented by rabbits; there were colonies of them on The Downs. The overseer used to go out on a regular basis, so we had rabbit at least once a week, roast rabbit or rabbit pie, which was absolutely gorgeous. My father kept bees, chickens and ducks and not only for the eggs but for the hens as well. We also grew runner beans and tomatoes. I have never tasted tomatoes like the ones he used to fertilise with elephant poo! Tomato sandwiches were absolutely delicious! My mother always mixed the two rations of butter and margarine together and it wasn't until I was at college that I realised what butter tasted like on its own!

We used to go out into the fields and gather in the grain; put it into sheaves (there were about seven sheaves in a stook) and splay the legs out so that the rain would run off them. We worked late into the night and ended up with very scratched arms. The dry stalks were cut off and used as animal straw while the grain was taken to the works yard, thresher. My job was to fill the oat sacks; I never thought that I would encounter a rat or a mouse; otherwise I probably wouldn't have done it. They were then taken down to Eaton Bray with me standing on the back of the lorry for a ride!

In January 1940, a black rhino and an African elephant both died as a result of a very severe winter. The ground was so hard they couldn't dig to bury them so they were burnt in one of those flint pits that used to run along the front of the Downs; it took a week for the carcases to burn. Food was very scarce and during the first Christmas of the war a polar bear had a cub and its father ate it. A litter of tiger cubs and a giant panda all had fits and Boxer the two year old giraffe, became ill. Visitors to Whipsnade were encouraged to bring food for the animals. They were asked to bring lettuce, cabbages and carrots for the herbivores, buns for the bears and sugar and buns for the elephants - I always had acorns in my pockets, they loved those. The one animal that didn't need feeding was the wooden horse; it stood on the top of the Downs. It was going to be broken up but a group of admirers saved it and brought it to Whipsnade in 1937 where it stayed until 1947.

Whipsnade was an air- raid warning post; warnings were phoned to the estate office (which was also the headquarters of the home guard and the civil defence), and passed to Kensworth and Studham. There was a hooter on top of the water tower, which always sounded at five o'clock so that wherever the works department were, they knew it was time to knock off and go home. That now became the air-raid siren and every time it sounded the wolves howled in unison!

About 41 bombs fell on Whipsnade between August and September 1940. My friend and I were cycling down Incinerator lane, which runs from Whipsnade to Studham, so called because it was where the incinerator was located for all the zoo's rubbish. We then heard this terrific bang, looked up and saw this silver plane and a puff of smoke - we thought we were being bombed. We flung ourselves into the hedge. The bombs that did land in the park didn't do much damage; mostly they made craters that eventually turned into ponds. The only fatalities were the Spur Winged Goose, the parks oldest inhabitant and a baby giraffe that panicked and ran itself into exhaustion.

In 1945 I remember falling off the snow plough and was caught by an Italian POW. We had 2 Italian POWs helping out at Whipsnade. We had a bonfire on the common when the war finished on the 8th May. I finished the war with an absolute flourish, because on VJ night I tipped Gerald Durrel headfirst into a cow pat, not knowing how famous he was going to become.

The war was a very exciting time for me; the only really serious parts were the shortages of food for the animals; animals that had to be burned at the beginning of the war and seeing the bombing of London.

Abroad for the First Time

Contributed 20 May 2005 by Stuart Hammond

My name is Stuart Hammond, I was 13 and a half when I listened to with my parents to the radio on the 3rd September 1939 and heard the Prime Minister, Mr. Chamberlain, informing us that a state of war existed between Germany and ourselves. This news was received with great dismay, as at this time the nation was still recovering from the terrible events that cost us so many casualties in the first world war only 20 years before.

My name is Stuart Hammond, I was 13 and a half when I listened to with my parents to the radio on the 3rd September 1939 and heard the Prime Minister, Mr. Chamberlain, informing us that a state of war existed between Germany and ourselves. This news was received with great dismay, as at this time the nation was still recovering from the terrible events that cost us so many casualties in the first world war only 20 years before.

There is no doubt that the Spanish civil war and the bombing of Guernica by the German air force a few years before convinced the Government that the Germans might well bomb London early on in the war and an evacuation of children from London was ordered a few days after the 3rd September. I found myself saying goodbye to my mother at a railway station near to my school, the Acland Central, Kentish Town, in north London. I was joining thousands of other children, on a journey to an unknown destination, carrying a small suitcase and a cardboard box containing my gas mask, and wearing an identity tag around my neck.

After a journey lasting a couple of hours the train pulled in at a station in Bedfordshire named Leighton Buzzard. We all got off the train and our teachers directed us to a grassy bank outside the station to await allocation to foster parents. We were all given a large bar of Cadbury's chocolate! I was eventually ushered with eleven other boys onto a coach and we were driven a few miles to the village of Great Billington. We were now in sight of where we would be sleeping that night - the rectory. This and the Church were on top of a steep hill and we found we had been taken in by the vicar's wife. We must have been a pretty tired bunch of lads who laid down that night on mattresses on the floor of the attic of this large rambling house surrounded, as we were to discover the next morning, by a large garden and with a marvellous view over miles of countryside.

The main view south was towards the Chilterns, and closer to us a large acreage of plum orchards in Eaton Bray. The weather was sunny and warm and being early September, the plums were ripening and being so plentiful we ate a lot of these sweet and tasty Victoria's. Unfortunately many of had stomach ache through over-eating .

Our accommodation was only temporary as there was no school large enough in the village and within a few weeks we were transferred to Dunstable. Here I was billeted with new foster parents. They were a retired couple and strict Methodists. For the first time in my life I was given a room of my own. Their name was Mr. & Mrs. Herbert and I was looked after very well. Food was not plentiful but Mr. Herbert was a keen gardener and we never went short of vegetables and soft fruits. I was introduced to bread pudding, which was good filler for growing lad.

There was a large modern senior school in the town and we integrated with the pupils already there although sometimes we had to take our classes in various halls elsewhere in the town. We settled down to study for the School Certificate, which we would take in our 16th year.

After arriving in Dunstable we entered a period called the 'phoney war'. London was not raided straight away and some of the evacuees began to drift back to their homes in London - against government advice of course. The children were missing their homes and parents - and perhaps not too happy with their new homes - and I too succumbed to the temptation to return. It was with the consent of my foster parents that I made one journey back to north London by train and two by cycling. I would leave on a Friday afternoon and return on Sunday. The A5 was a busy road and I managed the journey without mishap. It was a fairly easy journey when I reached Barnet as it was downhill all the way to my home, but coming back was a bit hard -no multi-geared bikes in those days!

After the Battle of Britain in 1940 when we stood alone in defying Hitler, the air raids on London began. The town then began to fill with people who had been bombed out or trying to escape the terror of the air raids. My own parents arrived and were lucky to find a cottage to rent. By now I had got used to living with Mr.& Mrs. Herbert and was quite happy with them and they with me - and the expectation by my parents that I should come to live with them caused me and my foster parents some heartache. However, I had no option but to leave and live with my parents. Soon the small cottage became quite crowded when my mother's sister and her mother were bombed out and they also came to Dunstable to seek refuge and respite from the raids.

When the raids subsided our guests found a property in Cuffley to live in and my mother and I were on our own again, my father being away in the Army. My mother worked in factory producing bomb sights for our bombers.

I left school at the age of 16 and spent the following two years as a junior clerk with the publishing house of Macmillan situated in a narrow street behind the National Gallery in London. At the end of this period, at the age of 18, I received my 'calling-up papers' and had to leave my job with a promise that it would be available to me when I returned from the forces.

The instructions I received required me to report to the RAF at Cardington in Bedfordshire in mid-May, 1944. I had belonged to the RAF Cadet Force soon after leaving school and having been given the choice I opted for the RAF to serve in.

The weather during the next few weeks was warm and dry as I was initiated, with hundreds of other recruits, into the routine of parade ground drills and route marching and living with 20 other chaps in a Nissan hut. All this came to an abrupt end however as we left for a more permanent location at Skegness. We had become used to the sight of the enormous hangar near to the camp that housed an airship, probably the only one in the country, and it was this that we could see for some time as we sat in the back the three-ton lorries taking us to the east coast.

It was now early June as we arrived in Skegness and we were allocated accommodation in requisitioned houses - quite an improvement on the huts we had at Cardington.. We discovered that we were here for three months of basic training, in other words more of the same but probably a bit more intensive, and this it certainly was as we made regular visits to the firing range and the assault course, and went on long route marches. There were about 20,000 recruits being trained here and we were all in for a big shock before long. "D" day took place within a short time of our arrival and there was much speculation that the war may be over before Christmas - the news was very promising at first but as our troops were unable to take Caen and got bogged down in the 'bocage', we were not so sure. In Skegness we were training hard and getting very fit, and most us were wondering when our training would start to be radar operators, aircraft fitters, and etc. Towards the end of the three months the bombshell was dropped. We all received a letter from the Air Minister to inform us that we would be taken out of the RAF and put into the Army instead. Astounded, but without any means to appeal, we accepted the inevitable and we were taken off to various Army depots to exchange our blue uniforms for kharki

The changeover was made in late September in Huyton, Liverpool, and I was put in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. I had no connection with Wales but got on well with my new brothers in arms most of whom seemed to be named Jones. From Liverpool we were taken to a camp called Eglington in Northern Ireland. Londonderry was a few miles away. We were trained in much the same way as we had been in Skegness but the route marches always seemed to cover, or included a night on, boggy peatland.

In December our training finished and we knew that our next destination would in Europe. In the Ardennes the battle of the bulge was being fought in severely cold weather, and it was just as bad with heavy snow in the town of Newport in Wales where we arrived in late December. After embarkation leave we were taken across the channel and I set foot on the continent for the first time. We went by train across Belgium and we de-trained at Louvain. A march through this old town took us to a large gloomy barracks where we were to be held and sent to where we were needed to push the Germans back across the Rhine. Conditions were very primitve and probably not much different from those when it was in use during the first world war.

A list was posted each day giving names of those who were to move out of Louvain. One morning a notice was put up requesting names of people who had had clerical experience and I responded. To my surprise I was accepted and posted to the 1st Bucks Battalion who were stationed in Brussels in another large barracks near to the centre of the city. My duties would be in the Orderly Room, HQ of the Bn. For the time being the prospect of being sent north to the front was lifted. However, in early March we were sent north with the task of escorting civilian scientists and specialists in uniform to the front and sometimes beyond to investigate sites of military importance with possible secret programmes including nuclear weapons, rockets and submarines. We were called the 'T' Force. Such was the speed of our advance towards the Rhine that we soon found ourselves in a town called Haaksbergen, recently liberated, near to the German border.

Within a few days of the war ending officially on 8th May, the role of the 1 Bucks Bn changed again and we became part of the occupation force as we crossed the border into the Ruhr and passing unimaginable devastation. We set up our HQ in a coalmining town called Kamen, beyond Dusseldorf. There had been a bad coalmining accident here recently with many casualties. There had'nt been much damage to the town and we were soon living in requisitioned houses and using the showers at the pithead.

Gen. Montgomery now changed the name of the Army from British Liberation Army to British Army of the Rhine. He also issued a non-fraternisation order which meant that we were to have no social contact with the Germans - this lasted six months.

The 1 Bucks Bn was disbanded and we were sent to a barracks in the Harz mountains, Bad Gandersheim, and put into another regiment, the 1st Bn Worcestershire Regt. Again my duties were in the Orderly Room. It was now 1946.

In the south, in Yugoslavia, Marshall Tito was threatening to take over Trieste on the shores of the Adriatic, and a large port. In response to this situation we were sent there to be on hand in case of trouble. And so I spent the next year or so in this area and actually moving for some months to Pula where I was promoted to Orderly Room Sjt.

It was from here in mid-summer, 1947, that I was given leave to return home to be married.

Soon after I returned to Pula the Bn moved back to Germany and we found ourselves in fairly modern barracks in Luneburg. In late 1947 my demobilisation number came up and I was sent back to York in the UK to be returned to 'civvy street'.

After the euphoria of being home again and out of uniform wore off it came as a shock to find that it was not going to be easy to find accommodation because of the housing shortage. I discovered that my job was indeed available to me with the publishing firm I was employed by before entering the army, but the wage they would pay me would be the same as I received on leaving. Now married with more responsibilities it was impossible for me to accept their terms and I looked around for another position. It became clear that jobs were few and far between and the future for a newly married couple was not going to be easy.

Farming and Life on Dunstable Downs

Contributed 1 December 2005 by Derek Bonfield

Contributed 1 December 2005 by Derek Bonfield

I was born on the 27th November 1924; so I was 15 when war was declared in 1939 on a Sunday morning, when my parents and I sat on the front lawn listening to the radio. I was born and brought up on Shepherds Farm along the Icknield Way when it was a poor time for agriculture. All the land had to be ploughed up and put into production. Up until then the ground hadn't been ploughed for many years, so father had to go and buy all the equipment to do this. The government paid you £2 if you ploughed up grassland and turned it into production. Although I don't think they paid for the machinery and we didn't get any grants.

We had pigs, cattle, hens, a horse and of course we had a great infestation of rabbits. We also had 2 dairy cows - house cows, my mother used to milk those and look after the hens. On part of the farm near the road was a field called the Chute. Over the previous years they had quarried chalk from there to make up the road. Afterwards, the council in Dunstable tipped spoil and rubbish into it, hence it was called the Chute. We used to see a lot of blue butterflies - Chalk Blues. The best part of the farm was the apple orchard in the valley. We used to put wire mesh around each apple tree to keep the rabbits off. In 1940 we had a very cold winter when the snow was quite deep covering the top of the wire mesh - this killed many of the rabbits.

We were controlled by the Ministry of War who made us grow potatoes. On one occasion this was an absolute failure - the potatoes didn't grow well because of the chalk soil. It was very poor and in places you could see the chalk on the surface. We used to grow corn and we'd under sow the corn with clover and then when the corn was cut, we also had a crop of clover to plough back into the ground. The petrol we used for agriculture was coloured red. It used to leave a red stain round the carburettor so you couldn't use it in your car.

I went to Britain Street School in Dunstable, leaving in 1938. I had one sister slightly older than myself; she married and went to live with her husband who was a manager on a big farm near Peterborough. In the early 1930s we had an influx of lads from distressed areas in the north, such as Gateshead. A lot of them lived at Cypress Hill where they had a house, a greenhouse and plot of land to enable them to be self-sufficient. They were in poor straits. If you were fortunate and had an apple they would follow you about and ask for the core; quite heart rending really.

Times were tough. The first service we had was a telephone; our number was 38! We didn't have electricity or water laid on but we did have a well which was 80ft deep. We used a rope to pull the water up which was clear and sparkling, lovely water coming out of the chalk. If you drew the water from the well you couldn't drink it straight away because it was so cold. We used to get cyclists stopping to ask for a drink but we daren't let them; we thought they'd get stomach cramps, it was so cold. There was another well in one of the fields near the Chute; 60ft deep where the water was equally nice - we used it for the cattle.

My father also had a haulage business, and in 1940 his driver left to work for Robins the whitening people. At the same time father was taken ill with rheumatic fever, so at 16 I went on the lorry delivering lime from Totternhoe to London and various other places. At night I worked on the farm, helping my mother. The lime was used to build surface shelters as cement would crack because it wasn't flexible, but with a lime mortar mixture, it held. They also used it to repair buildings that had been bombed.

I drove through Dunstable with the lorry every day in the war, but didn't really stop in the town. I used to take a lot of lime around the area of Cheshunt, Hoddesdon and Goffs Oak. The lime came from The Greystone Lime Company which was very busy during the war, with all production spoken for. The lime has very high silica content and makes good cement. They used it mixed with horsehair to make their own plaster on the building sites. It was live lime - quicklime. By the end of the war there was gypsum - plaster in bags.

One night, one of the lime kilns exploded. The fire door was quite large and heavy and worked on a pulley; it weighed 2 or 3cwt and blew out about 100yds. Fortunately the chap on duty was barrowing the ash away from another kiln that night and no one was hurt. They had to rebuild the chimney. In 1947 they acquired their own transport at the lime works.

As a boy I used to go up onto the Dunstable Downs to watch the gliders. Before the war we used to help launch them with an elastic rope. As many as we could muster would pull on the rope and somebone would hang onto the back of the glider. We used to walk, and then they would tell us to run, and then, run like hell! They would let go of the glider and you would fall in a heap. They were very basic things. They used to land with an enormous bump. They weren't gliders as such; they had a tubular frame and a bucket seat. I can picture the pilots now with their Oxford bags flapping in the breeze.

In the final stages of the war, the gliding club was turned into a POW camp. We had 2 Italian POWs to work on the farm and eventually we converted one of the stables so they could live on the farm. One of them had been in the Italian Air-Force and was educated at Oxford while his father was a Miller in Rome. His English was perfect with an Oxford accent, although he assured me that he used to fly very high and drop his bombs in the sea. We had no contact after the war.

The German planes used to fly up the estuary towards Fords (a huge factory manufacturing vehicles, and a prime target). The Becontree estate, made up of many roads of houses built for the Ford workers regularly had slates blown off their roofs. It was more dangerous in the latter stages of the war. I had a near miss with a rocket in London, it did my ears in. Everybody carried on though. There'd be a warning but everything would be operating, buses running and so on.

When the Met station opened in Dunstable there was a RAF chap named Sgt S, who hailed from Essex and had been a butcher in civilian life. He cycled by one day, saw all these rabbits and asked if he could come and shoot them. He used a .22 rifle and was a good shot. It was through him that we were allowed to harvest the hay around the Met Station. We had the hay in exchange for cutting it and keeping the place tidy for them. My father was up there one day with the tractor and mower. He liked to do a tidy job and was getting close to the mast; he then accidentally cut through one of the wires and the thing came whistling down. They very soon had it up again, though.

The perimeter hedge used to run down where Drovers Way is now, and I was up there mowing a piece we hadn't previously cut before, so father said keep tight to the hedge. While doing so the tractor plunged into a hole where they had put some phosphorus grenades but forgotten about them; fortunately they didn't go off!

It was all very hush hush, what was going on at the Met Station, we knew and referred to it as a Met Station but the actual running of it, we didn't know anything about it.

Most of our groceries were delivered from the International Stores. Mr P used to come round with a model T Ford and then later an Austin. I can see him slinging his money bag on his back now and cranking it up. He used to come late at night sometimes; I suppose we were last on his round. The baker used to come from Eaton Bray.

The biggest businesses in Eaton Bray were the glasshouses, growing tomatoes. My wife's relatives worked there in the war. It looked like a lake from up on the Downs. I think Mr Bates from Church Farm in Whipsnade grazed sheep on the Downs. There was a bomb dropped between the village hall and Poplar Farm in Totternhoe and there was a bungalow up a track near the Travellers Rest known as the Frenchman's house. I never saw the Frenchman, it may have been General De Gaulle, but it was isolated and I never saw anyone there.

I belonged to the Home Guard and occasionally we trained up on Totternhoe Knolls. Every Sunday morning and once or twice in the evenings we also trained but we didn't have rifles. We also did a regular night at the mill at Eddlesborough, up on the tower and we did night duty on the main road by the Plough. A shepherds hut was used as a guard hut. Any traffic was stopped, but there was very little. Parrots Lorries from Luton were the first things along.

The nearest farm to us was at Valence End, the next was Ebenezer's, where the RAF place was based at the Travellers Rest. It was a signals station but we never knew what its function was, mostly it was underground. We found that out when we carried out a raid in the Home Guard. The exercise was to capture it. We managed to get over the fence and we came across what we thought was an air-raid shelter; we climbed down, fell over a dispatch rider who was asleep in the passage way and found it all happening! We had achieved what we wanted. They were connected with the Stanbridge RAF station, a kind of sister station.

In 1948 father sold the farm and moved to Devon. I stayed here, I had married by then.

War Memories

Contributed 1 December 2005 by J C Horne

Contributed 1 December 2005 by J C Horne

When I was a boy I lived in the village of Stanbridge, not a lot going for it, we had four street lights plus a light on an arch across the Five Bells Drive where on dark nights we used to play under it.

Then the war started which meant no lights so it didn't affect us a lot. Mr Chamberlain declared war Sunday 3rd Sept. First thing my Father did, find some wood and felt to make shutters for down stairs windows, Mum finding thick curtains for upstairs so no chink of light showed. For a time life didn't change a lot until men started to be called up. If any bombs dropped in the area boys being boys we would cycle to see if we could find any souvenirs to collect.

Living in Stanbridge if you wanted to go to Leighton Buzzard you either had to cycle through Billington or through Egginton as the Leighton road was closed most of war because of R.A.F station. We still used to meet as normal at nights and sit on the seats on the green and listen to the bombers going over especially on the way to Coventry.

I worked at the nursery at Eaton Bray. Where they growed tomatoes and lettuce, not many flowers. The end of August 1940 there was a loud bang over Luton. Vauxhall had been bombed, the bombers were flying along the Dunstable Downs before the siren had sounded. When I was 17 I joined the Home Guard. Got kitted out with uniform, rifle and 50 rounds of ammo. Parades Sunday morning over Stanbridge Green, Monday nights Tilsworth Church House.

Some Saturday nights we had manoeuvres against other village with Guard duties once a month. (Every time I watch Dad's Army on television it's just how Stanbridge Home Guard was like). Doing the drill, firing a rifle prepared me when I joined up in 1942 in a little town called Harbury in Yorkshire for six weeks infantry training. I was then sent to Deepcut in the artillery for training on Bofor guns.

When training finished posted to 68th LIGHT AKAK REGIMENT. When we went on manoeuvres we gave cover to the 25 pounder guns, other times we would be on gun sited around the coast. When we were on a site at Deal the German guns used to send there shells over then our Coastal guns would open up to fire back so you could imagine the din they caused.

Landed Normandy end of June in the 49th Div but after about 3 weeks most of the infantry regiments had loads of casualties and the div was disbanded and I finished up in the Ox and Bucks L.I. 53rd Welsh Div. Through France, Belgium and Holland towards Arnhem to try and reach the airborne without success.

Later on the end of December back to Belgium to the Battle of Bulge. Finished up in KIEL when I was demobbed May '46.

A Comptometer Operator in Dunstable

Contributed 21 December 2005 by Mary Cumberland

Contributed 21 December 2005 by Mary Cumberland

My first recollection of the war happened when I was sitting under the trees in Grove House Gardens. I heard a bomb explode and saw a plane circling around; I think the bomb hit the Vauxhall plant in Luton.

I used to attend the church in Union Street where many evacuees were sent before being billeted around the town. I lived with my parents and we had evacuees and several other people staying with us that worked at the Met Office, in fact, we're still in touch with some of them now.

We always wondered when dad would be called up. When he eventually received his papers he didn't pass his medical fitness test, which mother was very pleased about but he served in the Home Guard instead. Luckily enough his unit was based in the golf club house on the top of Dunstable Downs; I think they quite enjoyed themselves up there!

My father also received a letter telling him that he had to go and do some kind of war work and was allocated a job at the Empire Rubber Company. He was made a foreman in the industrial trimming shop but he also used to bring home stacks of rubber work. We'd help him trim windscreen wipers and all sorts of other things. However, in 1936 he'd started selling insurance, so my poor mother had to do this insurance round every week. Sometimes I went with her and we cycled from Dunstable to Totternhoe, Eaton Bray, Eddlesborough, Stanbridge and Hockcliffe. On Friday evenings dad used to go with her and call on Houghton Regis and on Saturdays they went to Luton. I used to have to look after my sister, do the housework and get the dinner ready for their return. Mum was a seamstress and took in lots sewing, dressmaking and hat-work. For the hat making, she operated what was called a 17 guinea machine. Straw plaits were delivered to our house and she would sew them together to make hats. They were then picked up and taken to Luton to be 'blocked' - they were very fashionable in their day.

We were short of food in some ways but my dad had two allotments so we were never short of vegetables. Mum would cook potato and onion pie and we always had chickens in our garden and kept a cockerel for Christmas. Rabbits could be bought from the local farm and Mr H came from Luton on the bus. He used to come round to the back door of our house with a big suitcase full of things. I can't remember what was in his suitcase but I don't think he sold black market goods.

I left school in 1943 and went to work for Percival's in Luton airport. They made Mosquito planes; it was quite exciting seeing these aeroplanes. I even managed to sit in the cockpit of the first Mosquito that was built on the production line! While I was there a V2 rocket came over and landed in Luton. It was very frightening because we could see the vapour trail just above our office block.

We had superb dances in Dunstable town hall. That was a lovely building and they had wonderful bands playing there. It used to cost 1 shilling and sixpence to go in, but my uncle was sometimes on the door and very often I got in for nothing!

I'd had training in London to become a comptometer operator and in 1945 I found out about a job that was going at A C Sphinx in Dunstable. As I was doing war work for Percival's they weren't allowed to release me, so I had to go to an industrial court in Luton. A C Sphinx represented me and I won the day and began work in their comptometer office.

My Childhood in Totternhoe, Bedfordshire

Contributed 23 December 2005 by Alan Wilsher

Contributed 23 December 2005 by Alan Wilsher

I was seven years old when the war started and one of my earliest memories is going to school with a biscuit tin sealed with tape. This contained a supply of biscuits and other food, just in case we were stranded at school during an air-raid. This had to be taken and kept at Totternhoe Church School, Castle Hill Road, until the end of the war. In those early stages we also had to carry a gas mask. I can remember my baby brother's gas protector which was shaped like a large carry cot; this was placed on the table.

One morning I was walking to see my father who was employed at the Chalk Pits when the air raid warning sounded. A few minutes later I saw German bombers in the sky. You could tell the difference between our planes and theirs by the drone of their engines. I ran home and we (the family) took cover in the pantry, the safest place in the house.

I can remember two planes crashing in the village; one was a Blenheim Bomber that crashed on the right-hand side of Eaton Bray Road in Costin's field. I remember going down to the area soon afterwards. I believe the pilot was in the Womens Royal Airforce WRAF. She had been ferrying the bomber to another destination.

Later on in the war I vividly remember standing in my back garden at 32 Castle Hill Road watching a Spitfire, which was in trouble flying from the direction of Dunstable. It flew over my house, circled over the church, returned and came down in Tom Turvey's field, at the rear of Dunstable Cricket Club. I understand the pilot was Polish and escaped uninjured. He made his way to what we used to call Bates Houses at the bottom of Lancot Hill. The Spitfire was there for 3 - 4 days before it was taken away. I was there when they removed the machine guns and bullets from the wings.

I also remember one night when bombs landed in the middle of the road just past the Memorial Hall. Years later, we could still see where the road had been repaired and the telegraph wires were joined. That same night bombs fell in Totternhoe chalk pits near the lane to Sewell. Incendiary bombs also set Jessie Bird's chicken house on fire and a bomb fell near Middle Path at Eaton Bray. I always believed it was caused by a lone bomber who had got lost and was dumping his bombs before heading home.

I remember sledging up on Coxen hill, and night after night seeing the flashes of guns and explosions from London. Around this time, 5 or 6 lads from the village were awarded a certificate for putting out an incendiary bomb at the back of the Chalk Pits. I can remember in 1944, the hundreds of troops we had in the area. We had guns at the back of us in Castle Hill Road and there were also guns in the front of us in Sid bates field. We even had troops in the school playing field which was only an acre in size. A family had a dog which was always chasing Bren gun carriers as they went through the village. The whole area was a mass of troops. They used to fire the guns and practice firing into the chalk pits on the right hand side where the lane went down the incline. There were also a lot of troops down the Baulk and once a petrol truck was set on fire. The search light was down there. When D-Day came all the troops disappeared.

Village Life

Contributed 29 December 2005 by Jim Knight

Contributed 29 December 2005 by Jim Knight

One of my earliest memories of the war is being taken to Luton by my mum. She told me that we had to leave well before 5.00pm, as all the buses were classified as 'workers priority' and were often full up as they called at the factories before arriving in the town centre. I was also told to hold onto her hand very tightly when the bus came because everyone pushed forward and fought their way on, (no queues then).

Some of the older single-decker buses were converted to standee vehicles, i.e. seats were placed around the sides of the vehicles, facing inwards, to allow more standing room so that single-deckers could carry the same number of passengers as a double-decker bus. On the rare occasions we came home on the bus in the black-out there were no street lights. The blinds were pulled down over the windows at the front so you had to keep a sharp look out to see where you were. The interior lights had deep shades fitted making it very gloomy inside the vehicles at night. The conductors were provided with a little light in the ceiling, shining vertically downwards, also fitted with a deep shade, which could be pulled along so that fare collecting was made easier.

One Saturday afternoon my friends and I were playing on a grassy bank at the junction of Eaton Bray Road and Castle Hill Road in Totternhoe, when an Eastern National double-decker bus came from the direction of Stanbridge, (which they never did normally). It was filled with children, many leaning out of the window shouting, screaming and waving. Later at about tea-time, a village lady came knocking on the door with a little boy in tow. She told my mum that she had to take the boy in. He was an evacuee. Mum said we had no room in our small two up, two down cottage, with Mum, Dad and us three boys. After an argument with the lady, Mum gave in on the understanding that he only stayed until another house could be found. He actually stayed with us for several months before returning to London.

The older boys and girls who had moved up to Britain Street School in Dunstable came back to Totternhoe School for their final summer term, to ease congestion in Dunstable Schools. Many children evacuated from London schools had moved to Dunstable. The Ackland schoolchildren were based at Britain Street. These older children were often sent unsupervised on to the Knolls for walks in fine weather. For our safety we had to practise evacuation from the school in case of air raids. Miss B, herself a refugee from Jersey, would read to us in the afternoon as we sat around under a tree in the school playing field. The weather always seemed to be fine in the summer.

A Spitfire landed in the field near the Cricket Club; armed sentries were posted to guard it. A Blenheim bomber ran out of fuel and landed in Costin's field by the road to Eaton Bray. Two bombs dropped in the road near the memorial Hall creating large craters which closed the road. An oil bomb dropped in fields between Totternhoe and Billington. It made a huge bang. I remember my two brothers and I were in bed and it seemed in two seconds flat we were downstairs with our parents who were still up.

My Dad worked from 6am-6pm Monday to Friday and 6am-4pm Saturday and Sunday at the Totternhoe Lime Company. As a lime burner on the kilns he was in a reserved occupation. In addition we had a large garden and two allotments down Stanbridge Road at Ditchlong. We boys helped with the digging in spring and picking potatoes in the autumn. Dad kept a lot of rabbits which were killed to make pies and stews. We boys had to fill 2 sacks of food which we picked up on the Knolls for the rabbits each day after school and before tea in the spring, summer and autumn. Many people took allotments to 'Dig for Victory', which was a slogan in the war, although they knew very little about vegetable growing and would ask the seasoned gardeners for help. On summer evenings later in the war, as we toiled on the allotment, the sky was often filled with bombers going over. I can remember my Dad taking me to the look-out post when he was fire-watching and showing me the glow over Dunstable Downs as London burned.

Some village boys like me, got jobs helping with the harvest. I used to lead the loaded horse and carts from the field to the farmyard. Bigger boys pitched sheaves on to the carts. Later when the threshing machine came, wire netting was put on posts a little distance from the ricks being thrashed. It was put all round us boys who were given sticks; the farmer's terrier dog was also put inside the netting. Our job was to kill the rats. We also went stoking - putting the sheaves of corn into stooks to dry as they came off the binder.

We had army manoeuvres - long convoys of vehicles going slowly by with soldiers crouching down round the back of our house and in the garden. Army despatch riders came to train on the Knolls with their instructor. Anti-tank gunners came to practise in the quarry. The engine shed for the narrow gauge railway was in the middle of the quarry with the track of a falling gradient leading away. A winch was placed in the shed and a target was rigged up on the chassis of a wagon so that the target moved for the guns to aim at, the shells thudding into the quarry face. There were reports of ricochets into the village.

Later, Italian POWs came to clean out the brook; they coked a potato pie and gave us some, and when we got home we couldn't eat our dinner. Mum was not impressed. These POWs worked at the Lime Works and with the threshing machine. Later, German POWs did much the same. Land Girls also helped out on the farms, some even living in.

Ivinghoe Beacon was used during the war for firing ranges and gun practice. Some boys from Eaton Bray went there shrapnel collecting. While waiting for the bus home a live round they had collected exploded, severely injuring some of them.

Childhood Memories of Wartime Dunstable

Contributed 11 January 2006 by Albert and Patricia Morgan

Contributed 11 January 2006 by Albert and Patricia Morgan

On the first day of war, just after the Prime Minister made the announcement, the air-raid siren went. One of the first things I said was, "Where's my gas mask?" After a while, nothing seemed to happen and everyone began opening their front doors to see what was going on. Just along Edward Street was an air raid warden post and after a few minutes these apparitions in yellow capes, trousers, Wellington boots, service gas masks and big rattles appeared walking up and down the street. The only other time I saw them wearing all that gear was when they had safety demonstrations on the Square outside the Methodist Church. It was quite an eye opener for a six year old.

We had a school billeted with us at Burr Street and soon settled down to attending mornings one week and afternoons the next. Two Polish boys were billeted near us; they could speak German and used to do imitations of Hitler. They put one finger under their nose, held their right hand in a Nazi salute and jabbered away in German. It was all very amusing. Some children went back to London but others billeted in Victoria Street stayed all through the war.

There were various places that we liked to play, Grove House Gardens with the swings, slide and roundabout or Bennett's Rec. One of our favourite places was the old car park, a walled garden all overgrown with apple trees, hawthorn bushes and wild roses.

The fire station was built near the A5 past Anderson's, where they sold uniforms for the Grammar school. There was a large hard standing outside the station with a huge static water tank. It seemed to be like a big swimming pool, covered with wire netting around the edges. They also built a tower out of steel tubing where they'd hang the hoses to dry. Every day during the blitz you could see the hoses because the AFS, later the National Fire Service, were sent to London from Dunstable to fight fires. My uncle was in a kind of fire brigade at Waterlows and was drafted into the AFS/NFS and stayed there throughout the war.

My father was Sergeant Major of D Company and when they moved on, all the flags, bunting and some of the office furniture was distributed. We had a chair and a big chest full of flags and bunting. D Company were moved from the 5th Battalion to form the nucleus of the newly formed 6th Battalion Beds and Herts. My father went with two of his half-brothers, one of whom was the commanding officer's batman, and the other a squadron/platoon runner. They were moved to guard the radar station at Bawdsley, Woodbridge. They were then moved to Almouth in Northumberland to guard RAF Bulmer on the cliffs. My mother laughed - she had a postcard from my father saying, "I can't tell you where we've been sent to." But it was post marked Almouth! A day or two later Lord Haw Haw announced on the German radio that the 6th Battalion had been moved to Almouth. So much for security.

After this my father was moved to the Royal Fusiliers. He was in several battalions, carrying out office work to set up a new battalion. He was acting RSM but paid as a WOII. He did this for a couple of years before going to the officer cadet-training unit. When he'd completed the course, he was commissioned into the Pioneer Corps. He was involved in looking after troop movements and was second in command of a POW camp on the Welsh border in Herefordshire. He used to come home whenever possible, about every 6-8 weeks for a weekend or a few days, but it all depended on what was going on. The army came first.

My Grandparents moved to Black Notley in Essex when my Grandfather retired, moving back to London in 1941. One day, probably in 1940, we had this suitcase delivered. It had come all the way from Essex by train and was full of damsons. They were a little bit ripe but there was some sugar available, so damson jam was made. Toys weren't that easy to come by, so we made our own, perhaps had a stick and a rim of a bicycle wheel. One lad had a steel hoop and a hook and we had whips and tops. We made little tanks out of cotton reels, an elastic band, a slice cut from a candle and a matchstick; we had races with those. It was all good fun.

At the beginning we weren't all that aware of what was going on. Then came the blitz. It was possible to stand in the middle of the road in Victoria or Edward Street and see a red glow and flashes in the sky over London. Black-out boards were put up against the windows. We tended only to use the living room at the back of the house and the kitchen. It was easier to use one room.

When my sister was old enough she joined the ATS. Both the ATS and the Army didn't provide rations for weekend leave (they did for proper leave). If Dad was told a day or two before, he could usually wangle something from the cookhouse. My sister was stationed at Gower Street in London and she could usually bring a little extra home in her gas mask case.

They used to test parachute flares on the Downs, and if we saw these bright lights when we had an afternoon off, we would dash off, get downwind, and hope to find one. The ones that came out of small mortar bombs were about 2ft in diameter, made of pure silk with a round block of wood at the end of the flare. They would perhaps be firing them off all day and I remember wandering to Kensworth once and there was a great crowd of children in the field. The big boys used to run underneath the parachutes as they floated in and they could jump higher than us and grab them.

One day there were two boys who were jumping up and on this occasion the parachutes were nearly 4ft in diameter, coming from the bigger mortar bombs. They were grabbing them with gloves on, and although they were smouldering, they could avoid getting burned. They ran across to a man and woman who cut off all the strings and stuffed the silk into carrier bags. A piece of silk that big could be used to make many things. They were firing them from mortars roughly opposite the golf club entrance over the slope of the Downs. Soldiers were stopping people from walking along the Downs or past the mortars while they were firing. The soldiers at the bottom of the Downs picked up the empty cases. The ones they missed, I collected. They were testing flares about twice a week.

My father used to buy aircraft recognition books. They were about as big as a notepad with about 20 or 30 aircraft in them. British aircraft were covered in about 4 or 5 books, German, similarly I think. Sometimes we'd see aircraft that we didn't know. We were in Grove House Gardens one day and some planes flew very low towards Leighton Buzzard; I found out later they were Westland Whirlwinds. I only saw them once but they were a striking aircraft. They had a Spitfire week where everyone was encouraged to buy savings stamps. In Grove House Gardens, in a marquee, was a ME 109. You could pay to go in and if you bought a savings stamp, you could sit in it.

Later in the war, the ARP carried out demonstrations. They'd have a building filled with straw and probably laced with petrol and a plane would fly down the high street from the direction of London; one night it was a Swordfish. They flew very low, about 3 or 400 ft and you could wave to the pilot and he'd wave back, and as it went past this hut, it would burst into flames. The wardens would dash forward, start on it with the stirrup pumps and then you'd hear the ding, ding, ding, bell of the fire engines. One of the auxiliaries or one of the main engines would dash round the corner into the Square.

There were posters around the town and in the school about butterfly bombs. These were anti-personnel bombs that the Germans dropped. A policeman brought the only one I ever saw into school. He was very worried about children collecting live bombs from the Downs, so he brought one in to warn us but he accidentally dropped it on the table and it fell onto the floor. It made such a clatter. Nobody thought there was anything in it. We knew he wouldn't bring a live bomb into school!

There were live AG Mortars fired at the back of Ivinghoe Beacon. After the war a few boys from Eaton Bray collected some. They were waiting at the bus stop and one went off. I worked with one of the lads who survived, I think 3 were killed and 2 survived. The bus was coming, they put the boys on and it went non-stop to the hospital. With my father being in the army he'd always said, "Don't pick anything up, always look to see if it's empty." We'd seen the empty ones with the nose-cap off and I don't think I ever saw one with the cap on.

After VE day, what was called the Women's Tea Committee from the Congregational Church in Edward Street, decided to have a street party. My mother, my Auntie Maggie and the lady next door went round asking people if they could spare a little margarine, butter, or a few points, because Miss R at the shop had said, "If you bring the points, you can have food for the party." At one house they struck gold, there were 2 young ladies there and they gave them tins of corned beef, a wooden keg of butter and some large tins of fruit cocktail and these were duly taken back to the Congregation. When a couple of maiden ladies saw them they said, "We can't possibly have those! They are the wages of sin!" They were all marked U.S Army. Maggie and my Mum said, "The children don't know about that sort of thing, they'll enjoy it." Of course it was a marvellous spread. It was a fine day and trestle tables and chairs from the church were put outside. Red, white and blue bunting was laid down the middle of the tables, all the church crockery was used, the Reverend officiated, said Grace, gave thanks for the end of the war and then we all tucked in.

The camp at the gliding club housed the POWs. Towards the end of the war the Italian POWs were allowed to come up into Dunstable. It was after the Armistice when Italy capitulated. However, there were Polish soldiers at the camp behind Grove House and fights broke out in the town. As a result the Italians were moved and replaced with Germans. They weren't allowed out until after the war and were used to build houses on the Beecroft estate. At the end of what is now Maidendale Avenue and Victoria Street there was a hut and on the door was a sign in German, which meant Works Manager.

Pat Morgan - The Italians were working on the fields at the bottom of Blows Downs and we used to spit at them. They used to get very upset, cry and say "Oh, the bambinos!" We were 5 or 6 years old and horrid. The evacuees were worse than us. I started school in '43, and they were amalgamated with us. We did 3 days one week and 4 the next. The Londoners didn't like the Germans or the Italians and encouraged us to do these awful spitting things, but we did like the American convoys coming through. If you put your ear to the ground as you walked down Priory Road, you could hear them coming from a long way off, and if you walked slowly with a bit of luck they were coming through before you got to Ashton school. You could sit on the high kerb on the church side of the road and wave and the Americans would throw sweeties.

Pat Morgan - The Italians were working on the fields at the bottom of Blows Downs and we used to spit at them. They used to get very upset, cry and say "Oh, the bambinos!" We were 5 or 6 years old and horrid. The evacuees were worse than us. I started school in '43, and they were amalgamated with us. We did 3 days one week and 4 the next. The Londoners didn't like the Germans or the Italians and encouraged us to do these awful spitting things, but we did like the American convoys coming through. If you put your ear to the ground as you walked down Priory Road, you could hear them coming from a long way off, and if you walked slowly with a bit of luck they were coming through before you got to Ashton school. You could sit on the high kerb on the church side of the road and wave and the Americans would throw sweeties.

By '43 or '44 there were an awful lot of troop movements. The Americans were billeted in Dunstable. The lady next door took in coloured Americans because not everyone would. She had 2 billeted on her and they were very nice fellows. I'd never seen a black man before, I was totally fascinated, Robert and Lloyd they were called. We were always told that if the Americans asked us if we needed anything, we were always to say toilet paper, not sweets. They did give us toilet paper, and sweets. They were stationed at the back of Moores, through the arch in what became the Index Publishers. There weren't that many of them but they were very nice.

It was Thursday September 12th and Mother was walking up the high street, heavily pregnant with my sister. She met a friend outside what is now the little theatre and was having a bit of a rest when an aircraft came down the road - bang, bang, bang! There was so much tree cover she was lucky. When she went into labour that night, she was certain that's what brought it on.

My Dad was at Vauxhall in a reserved occupation and was at work the night they were bombed. They hit the canteen and my Dad was so angry that he hadn't had a cup of tea. They had gone all night without a cup of tea because these ***Germans had dropped these **** bombs on the canteen, and he made a huge pot of tea, saying he didn't care how much he was using. After drinking his tea he went to bed, and then complained that he had to get up several times during the day, and our loo was out the back.

He was working in the experimental section at Vauxhall. They were producing Churchill's at the time when they were trying to stop sand affecting the engines. He was a machine setter but he was involved in technical stuff. He was also in the Home Guard and we used to try and get his Bren gun so he had it chained into the wardrobe.

I remember the fun. I lived in Great Northern Road and we used to go up on Blows Downs and play, we were away all day. Mum gave us sandwiches and a box of Ministry of Food orange juice. If the Home Guard were on manoeuvres we had to go home. To us, the war was quite good fun because we had no restrictions.

We went to the VE party in Great Northern Road and we also went to the VE party in Garden Road because we had 2 aunts living there who had no children. Park Road, Grove Road and Downs Road all had their own VE Day parties.